The Ultimate Insider

Howard was special. He read early, wrote early, he sang and danced and seemed to have a supernatural ability to charm adults. He was also a little effeminate. I have some family film of him at maybe four or five years old, dancing around just a little too high on his toes and a little too loose in his wrist. By the time he was twelve or so, Howard had gotten it under control and figured out how to play the part assigned to him but I know he took a lot of grief, especially in his early years. Our Dad was a good and fair man but he was a man born in 1920. I’m sure he would have been thrilled to toss a football around with his son, had his son shown the faintest bit of interest. I’m also sure his son didn’t show any interest at all and that Dad pretty much rolled with it.

Our grandfather, Mom’s dad, wasn’t so easy going and I know at one point in Howard’s youth, Pop pop (yep, that’s what we called him) took Howard aside and told him to act more like a man – for his father’s sake. I also was told that Dad took my grandfather aside soon after and told him to lay off his son.

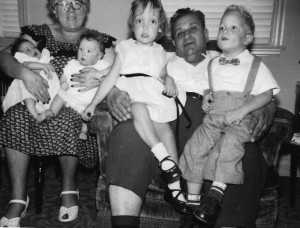

Still, it was our grandparents who, maybe more than anyone, encouraged Howard’s love of theater and art. This was not entirely because they wanted Howard to fulfill his dreams. This was pride, pride in themselves for being this kid’s grandparents. A pride, no doubt, that did no favors to the kid himself as they paraded him around to friends and relatives, saving every card, every program, every clipping.

There’s still a ringlet from Howard’s first haircut in one of the many photo albums our grandfather made.

Not all adults were so enamored. One neighbor lady (we’ll call her Mrs. B) was especially furious when Howard took back from her daughter a role in one of our backyard theatricals (hey, if you’re not going to show up for rehearsal, you’re not in the show…even if the show is a nickel-a-head backyard extravaganza).

Mrs. B stormed into our living room while Mom and Dad were both at work and berated Howard in no uncertain terms. She let him have it – that he was full of himself and selfish and should think more about other people. Maybe one of the problems of being a kid who acts like a grown up is that grownups themselves sometimes forget that you’re just a kid. And maybe one of the problems with being a kid with aspirations of greatness is that you have no patience for those who do not share your goals. Mrs. B’s daughter just wanted to be in a show. That wasn’t good enough for Howard.

I’m sure Howard got mixed signals pretty often. The adults in our lives liked the reflected glory of this little kid who was running around impressing teachers and getting cast in local shows. But when he was given an intelligence test and asked Mom how he’d done, she told him,

“Well, you’re no genius.

And he wasn’t. But he was very special – which can be wonderful and can be a burden. For sure, it can make you an outsider. In 1960, a gay ten-year-old boy in a working class home definitely qualified as an outsider. But in 1963, as a straight ten-year-old girl in the same home, I also felt like an outsider.

And I’m betting that since you’re reading this, regardless of whether you’re gay, straight, bi, trans or indifferent, you felt like an outsider when you were ten years old, too.

What Howard found, what many others have found, was theater -- the ultimate insider club for outsiders. It’s not a fix for everyone, it wasn’t for me, but when it works, it really works.

I think that sense of being an outsider informs much of Howard’s work. Every character in Little Shop, even Orin, is an outsider. Eliot Rosewater is one, too. Ariel, Belle, the list goes on. That’s what we all respond to.

I once told Howard that he was the only person I knew who got better with success. He became a nicer person, quite frankly. I don’t believe he ever got over being an outsider but like all of us who feel a little odd, a little off center, a little different – boy did he celebrate when the insiders finally invited him to the party.