Reliving "Howard"

By Kyle Renick

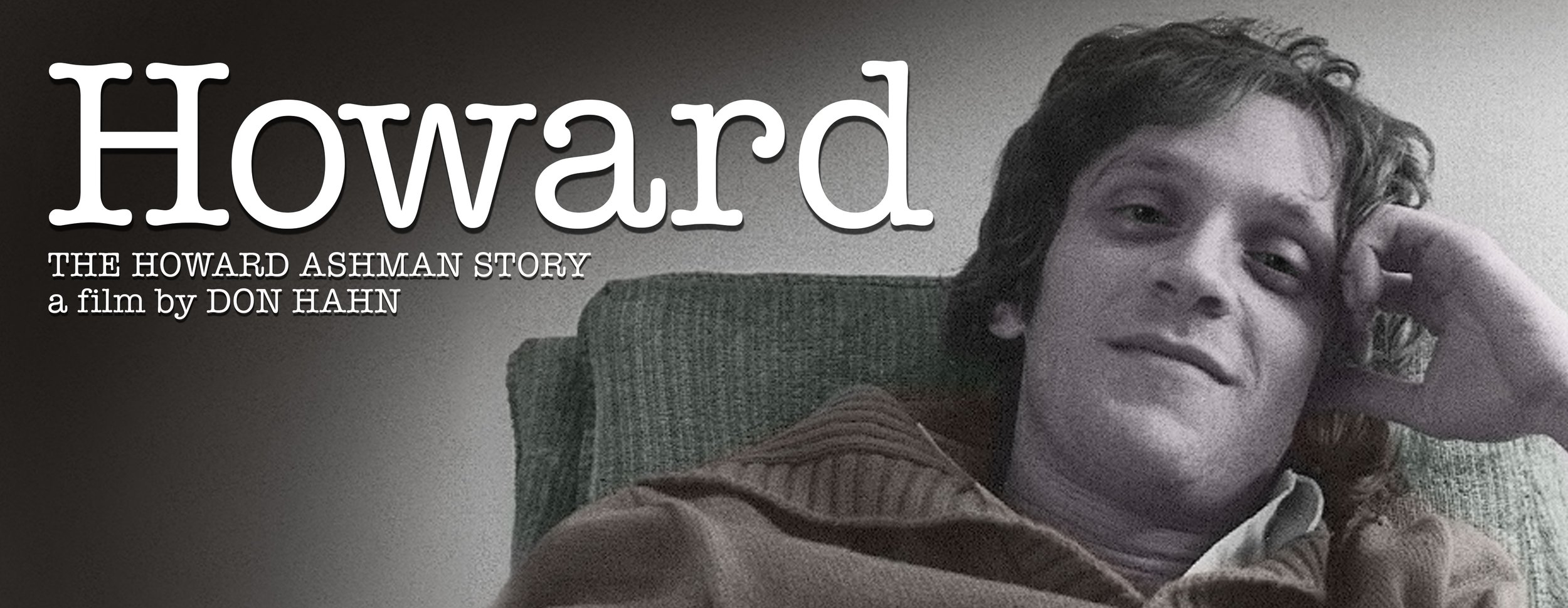

(note: Kyle Renick is a music critic for Film Score Monthly - this article was originally written for that publication. Renick was a friend and colleague of Howard Ashman. His photograph, taken in 1976, is used on the poster of "Howard".)

The taxi driver told wonderful stories about local wildlife, such as minks, lynxes, otters, weasels, mountain lions, packs of coyotes organized into clear tasks, and very old tortoises large enough to pull a small deer into the water as it was drinking. I felt ready for the Chinese metal dragons decorating the front gates of Alan Menken’s country estate in North Salem, New York, and the signs about driving carefully for the animals, although I promptly confused a statue of a deer for the real thing.

I had taken a train from New York to interview Alan Menken about his new score for Don Hahn’s documentary Howard, which will receive its world premiere next month on April 22 at the TriBeCa Film Festival. In the unlikely instance there is an FSMO reader unfamiliar with the Menken chronology, he is the recipient of eight Academy Awards, for Best Music (Original Score) and Best Music (Original Song) for The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin and Pocahontas. The lyricist of the Oscar-winning songs “Under the Sea” and “Beauty and the Beast” and Alan’s long-time collaborator was Howard Ashman, whose tragically early death of complications from AIDS on March 14, 1991 deprived audiences, friends and family of untold musical and lyrical wonders.

The taxi driver told wonderful stories about local wildlife, such as minks, lynxes, otters, weasels, mountain lions, packs of coyotes organized into clear tasks, and very old tortoises large enough to pull a small deer into the water as it was drinking. I felt ready for the Chinese metal dragons decorating the front gates of Alan Menken’s country estate in North Salem, New York, and the signs about driving carefully for the animals, although I promptly confused a statue of a deer for the real thing.

I had taken a train from New York to interview Alan Menken about his new score for Don Hahn’s documentary Howard, which will receive its world premiere next month on April 22 at the TriBeCa Film Festival. In the unlikely instance there is an FSMO reader unfamiliar with the Menken chronology, he is the recipient of eight Academy Awards, for Best Music (Original Score) and Best Music (Original Song) for The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin and Pocahontas. The lyricist of the Oscar-winning songs “Under the Sea” and “Beauty and the Beast” and Alan’s long-time collaborator was Howard Ashman, whose tragically early death of complications from AIDS on March 14, 1991 deprived audiences, friends and family of untold musical and lyrical wonders.

I told Alan that I hear both childhood and discovery in his two main themes, which he then played for me on the keyboard in his spacious studio. “The main theme is for Sarah’s [KR: Sarah Ashman Gillespie, Howard’s sister and a major character in the documentary] description of Howard’s making a little theatre in the bedroom of their childhood home, like winding up a music box, but letting the floodgates open up at the end. One theme is childlike, the other theme is about mortality. “After Howard’s passing, I was working on a song that I was calling ‘My Old Friend’ in his memory. I was in the process of completing the lyrics for that song, when Tim Rice [KR: Alan Menken’s lyricist/collaborator after Howard Ashman’s death] and I began collaborating on additional songs for the Broadway production of Beauty and the Beast. When Tim and I were working on a new song for Belle to sing as she becomes reconciled to her life as a captive in the Beast’s castle, it occurred to me that the melody and accompaniment for ‘My Old Friend’ could work beautifully for the phrase ‘Is This Home?’ And it also occurred to me that it would be fitting and appropriate to let that piece of music live forever in the musical that Howard and I were working on at the time.”

Alan then made an important observation about scoring a film. “Syncing my music with the rhythms of director Don Hahn.... It’s very liberating once a composer gets that that is part of his job. You want to support what’s being said and stay out of the way, to amplify the emotions and not express your own feelings. Chris Bacon went into the studio with Don Hahn to do whatever he needed.” Alan played a couple of examples of how Chris emphasized textures for the mixing and getting the right tone for a scene.

A few personal reactions came through, such as my favorite cue being the one for WPA Theatre, in which I hear clearly a sense of Howard coming into his own as a creative force, through development of one of Alan’s principal themes. “This is a more sustained melodic cue for a sense of forward motion in Howard’s life and work.” When I asked about the ostinato leading into a thematic treatment in the cue “Howard and Stuart,” Alan responded, “Howard and Stuart, Howard and Bill—the personal attachments of Howard—the music hopefully takes us into a feeling of Howard’s spirit rising.” [KR: Stuart White was Howard’s partner from 1970 to 1978 and a WPA co-director; Bill Lauch was Howard’s partner from 1984 to his death in 1991, and accepted the posthumous Oscar for Best Song “Beauty and the Beast” on March 30, 1992.]

There is a song I remember fondly from the WPA production of Kurt Vonnegut’s God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater—a number called “The Rosewater Foundation,” Howard’s handwritten lyrics for which we see in close-up in the documentary, as we hear part of the song performed by Howard and Alan. Commented Alan, “The first moment of sitting in front of a Howard Ashman lyric is like nothing else.” That kind of bliss is also registered strongly in the film’s first scene, of Angela Lansbury and Jerry Orbach recording part of the soundtrack of Beauty and the Beast, with both Howard and Alan exhibiting a sense of happiness almost impossible to define but clear to see. Alan smiled and nodded in agreement when I told him that this feels like a moment of “pure musical theatre heaven.”

It would be implausible that I have no disagreement with the narrative of Howard, and there is one, having nothing to do with Alan Menken and his score. After the success of Little Shop of Horrors, a collaboration between Howard and Marvin Hamlisch on a musical adaptation of the 1975 film Smile, a long-cherished ambition of Howard’s, resulted in a workshop at Michael Bennett’s famous studio 890 Broadway. That workshop, with pom-poms but no scenery and “staged reading” direction, was transformative and masterful, a tiny theatrical miracle, emblematic of how Howard Ashman could create theatrical magic with limited resources. But Gerald Schoenfeld of the Shubert Organization unaccountably refused to proceed with a full production. It is incorrect that David Geffen prevented the workshop’s Broadway transfer. Additionally, Howard knew almost from the beginning of the subsequent Broadway production that it was doomed, and he felt increasingly out of control on a hugely expensive white elephant. I stood with Alan Menken at the opening night party, realizing Howard’s nightmare about the production—and its press reception—had come true. Howard told me he would never go through this again. Peter Schneider of Walt Disney Feature Animation made it possible for Howard and Alan to move to Los Angeles.

The triumph and joy of Howard and Alan’s resuscitation of the moribund Disney animated feature film production is brilliantly captured by director Hahn in Howard. The stark and somber contrast created by the onset of Howard’s illness is heartbreakingly unavoidable. “The Mob Song” from Beauty and the Beast has an undeniable connection with then-omnipresent homophobia and fear of AIDS:

“We’re not safe until he’s dead/He’ll come stalking us at night/Set to sacrifice our children to his monstrous appetite/He’ll wreak havoc on our village if we let him wander free.” Thomas Schumacher, President of Disney Theatrical Group, is quoted saying, “You can never take Beauty and the Beast away from the AIDS epidemic.” The film includes this dedication: “To our friend Howard, who gave a mermaid her voice and a beast his soul, we will be forever grateful.”

The moving conclusion of Howard is his sister Sarah commenting, “Howard was about empathy.” When I asked Alan about that moment and his score cue entitled “Empathy,” he immediately said, “I’ll give you an example. I was getting an award at BMI. I was thanking everyone. And Howard said, ‘May I suggest we toast Janis?’ His antennae were longer.” [KR: Janis Roswick, former ballet dancer and Alan’s wife of 45 years]

My final question for Alan was, “What do you hope viewers will take away from Howard, especially those who never knew him?” He answered, “They should certainly take away knowledge of a man who was the single most important theatre/film/songwriting talent of our time. The world landed at his feet. When I asked him if he had any ultimate dream, he answered ‘I’d really love to start a children’s theatre group’.” My own answer in Howard is that I have been waiting all my life wondering if I would ever meet someone as talented as Howard Ashman, and I never have.